I first saw Doctor Atomic in the HD Live MET performance, which was an interesting intersection of opera and technology in and of itself. At ten in the morning Pacific Time on a Saturday, Megan and I dragged ourselves out of bed and down to the mall multiplex, where we purchased popcorn and sodas, and sat upon a completely grey-haired audience to see live opera beamed by broadband in digital high-definition from the MET in New York to Portland, Oregon.

There are probably some pretty heady archetypes flowing in that alone, but we'll leave it generally alone right now. Let me just say, as much as I love to get dressed up and go out to the theater, ballet, opera, etc, it is pretty awesome to see one of the best opera companies in the world perform in crystal, digital clarity for twenty bucks within walking distance, while slouching in my seat and eating popcorn, besides. Sure, people my own age are more interested in seeing the next comic book movie, but hell, as long as they keep doing the HD Live series, I'll be checking it out. We also saw Faust, which was great, but I do have the complaint that sometimes they do too many close-ups with the camera work, not letting me fully take in the amazing sets.

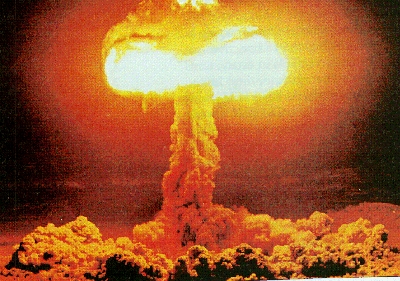

But let me talk about Doctor Atomic. It has been pretty well talked up in the media for several deserved reasons--for one, it is a new opera written about a modern-historical theme (Oppenheimer and the Trinity test of the first atomic weapon); two, it is actually a remarkably fantastic opera, already performed in three cities since it's premiere in 2005, leading many to speculate it may be a new canonical piece of work, which in these times of pretty shoddy additions to the canon, is nothing to sneeze at.

I, for one student of history and amateur opera appreciator, think it is a masterful work. While I hate to predict the future, speculating about this piece joining the ranks of works like Doctor Faustus is intriguing, and interesting on several points. Keep in mind as I speculate, I know very little about the dynamics of the aria, and am focusing on the liberetto, which is really for the best of all concerned, my musical knowledge being what it is.

Opera, of course, is a medium bursting with archetypes. Even more so than our most famous plays we find in opera the most characteristic plots, themes, and characters, if for no other reason, because the production's bombastic incorporation of full orchestra, magnificent costumes and sets, and the extreme ranges of the human voice lends itself to the biggest, the loudest, and the most impressive. But even more than that, it is straight-forward, direct, and without any irony, which in this day and age is a sort of victory for the form in its own way.

The canonical operas include archetypes of many sorts, incorporating, dramatizing, and commenting on the range of human behaviors. Doctor Atomic does no less, but this is not simply the reason for my enjoyment of it. It guides its archetypes, explores them, and for lack of a better description, puts them on stage and let's them perform the crap out of themselves for two acts.

The main archetype, in my estimation, is that of fate. I am not big of speculations of fate, myself. I have my own appreciations of the metaphysics of time and space, which are not really relevant here, but it strikes me nonetheless as a useless to worry about whether or not there is such a thing as free will. This is not the archetype we are dealing with in this opera--not the struggle of so-called free will against fate, in the classic Oedipal rejection of the will of the gods, or even in Hamlet's own struggle to accept facts and move on from there.

My favorite Shakespeare play has always been Macbeth, because I think it deals with fate most truthfully. Tragedy is unavoidable. This does not mean each person is destined for tragedy, or if one is predicted to have a tragic destiny there is simply no avoiding it. What it does mean, is upon being inflicted with horrible tragedy, there is absolutely no way to go back and say, "if only such and such had/hadn't happened, this tragedy never would have occurred." Causality, and hence tragedy, does not work in this way. Because tragedy was the result, everything previous can be seen as leading up to that. If Macbeth had never been killed, his encounter with the witches would have been just, "like, really weird, man." My images of Macbeth are drawn from Kurasawa's Throne of Blood, (because it is awesome). When the forest itself is coming to tear down the fortress, and when our man is stumbling down the steps of the towers, being filled full of arrows by his own men, it is not time to say, "gee, I never should have listened to that old man in the woods." That's fate for you. If you're fucked, you find it out when you're fucked. And then, simply, you're fucked.

And this is precisely the attitude we should be taking towards the atomic bomb. You and me, we're fucked. They already built the damn thing, and used it too. There is no point in debating historically whether or not it was a good decision. If you come to the conclusion it was a bad move... so what? It still exists.

And this is the moment we are at when the overature lifts, and the opera begins. "We believe that energy can become matter, and matter can become energy, and hence be changed in form." We know laws of physics. This is essentially a physical opera, because it deals with fate as fact, especially when it is historical fact.

I have read that the historical fact of the opera is not perfect. It does take creative license with the characters and some aspects of the plot, even though the liberetto is derived from almost entirely historical sources. But this is not the point either. The historical fact of the opera is the climax--the detonation of the Trinity bomb. This happened, and there is no going back. We have had over sixty years to talk about it, and the opera is only two acts long. But no matter what the actors sing, or what the audience concludes, the opera still ends in the same way: with nuclear fission. This is its, and our, fate.

But this was no act of god--hundreds of men worked to make this occur. We know this as well. We know the history of the war effort, even if few of us alive today experienced it. This part of the fate as well, a train moving forward, not out of control, but driven and directed by a mass of humanity.

The first scene begins with Edward Teller and Oppenheimer at a black board, doing math frantically. This opera's plot--the construction of the most powerful weapon in the world, which could in fact destroy the world--is naturally compared to other operas with similar magnitudes of plot. Wagner's Ring series also involves a weapon, and Faust also involved horrible, deadly, demiurgical power. But these are not titans, or fantastical beings forging a weapon on a hearth of hell-fire, nor magicians making deals with supernatural forces. These are scientists, doing math, extending their knowledge to the furtherest possible application of the rule in the physical universe in which they lived. The universe in which the opera exists is one of total war, when every person's efforts are devoted towards defeating an enemy with deadly force. They knew the Germans were working on the bomb, but after Germany surrendered, they first wondered about the direction in which this locamotive was heading, now that it was up to full steam. After Germany's defeat, the world could become social again--that is, concerned with social issues. This is a recovery from Auschwitz already beginning, even though the full depth of the horror was not widely known. Morality again comes into play, after the Reich falls. It comes back into play in both in self-judgment, and in judgment of others.

The title of the discussion the scientists have about the bomb goes by the almost whimsical name, "The Impact of the Gadget on Civilization". They got together and discussed, and some of them became active in their opposition of its use after it was created. Not that this was done in poor guidance of ineffectively, but the scientists were scientists, and not masters of social issues in the way they mastered physics.

Even at this point, an attempt to put on the brakes looks almost ridiculous from our perspective, in full awareness of what the fate will come to be. The bomb will be dropped, and it will be dropped because it was made. It was used on Japan for the rational reasons, to stop the invasion, to force surrender, etc. But as Edward Teller's line goes, "The more decisive a weapon is, the more surely it will be used."

Hiroshima was selected as a target for maximum casualties of a visible nature. This was not a weapon to use behind the scenes, or sneakily, or as a veiled threat. This is nothing less than the fated, Biggest Bomb, and it could never have been anything other than such. Seriously, can we imagine a world in which the atomic bomb had never been used as the weapon that it is? Can you imagine a world in which we had waited, and a war developed in which multiple parties had the bomb, and it had never been used? Perhaps the real fate, and the real justification (as much as you can justify anything in the past tense) of using the bomb was not for the Pacific War, but for all the wars in the future. Maybe we survived the Cold War by nuking Japan. But that's a lot of maybes and perhapses for a discussion of fate.

You can't justify or revoke any more than any of the scientists could have stopped what happened. It was simply going to happen, in our plotting of the events now, by virtue of the fact that it did happen. This is the fate we all have to deal with now, and this is the archetype--fate is what you have to deal with as its happening.

Gods, as we knew them, die on the day of Trinity. Humans become gods, uncapitalized. The opera is filled with religious symbolism and adapted lines, because this new archetype of fate--that we might have to deal with a fate so horrible as to destroy our world with a murderous deux ex machina rather than one of salvation--is not so much a reputiation of religion as a summation of it. You can forget the specifics of theology, but you had better remember the awesome horror of the cosmos. This is what the scientists discovered when they saw in a pillar of radioactive flame that all one really needed to have the destructive power of gods was to do an amount of math, and have the will to go through with it.

Hubris has nothing to do with it, and regret or forewarning has nothing to do with it. It is all about humans, their hands and their brains, finally completing the cosmology they had conceived of thousands of years ago in the bible, in the vedas, and in their other archetypical nightmares.

An interesting aspect of the opera is the fixation on the weather. They are waiting for the weather to clear so they can do the test; they are not sure if it will work, and they need to be able to measure the effects, and there is also concern about radioactive waste being blown back on the people. Despite their imminent fated ascendance as gods, these men still can't control the weather. They do not have the will of god, they only have the titanic weapons of physics under their control: and this, only barely so.

The power is not new; its the same duality of construction and destruction humanity has been wrestling with since the first ancestor clubbed another with a stick. It is simply that it has become the archetype, as it seems it was fated to do; suddenly with Trinity, we are able to increase the power of destruction/creation to the limits of our own imagination and understanding--which really is a pretty incredible thing. To imagine the limits and to exceed those limits in action. It is the occurance of fate--of the lining up of the mind and physical reality in a way that seems to say, "this is what is meant to be"... whatever that means.

In the atomic age, in seems we have surpassed many of the old archetypes, or rendered them irrelevant. Maybe this is why opera has been losing its hold on our culture. What could we possibly show in a set and with instruments that we can't see on the news, or hear warnings of in the news? Archetype has accelerated to reality, and we're left in sort of a stunned, modern haze, not really sure if we are fated to be here, if we have somehow violated a fated time-space and are stuck on a train running towards a cliff--or maybe such notions of our imagination about what things mean and are supposed to do are what is running towards that post-modern metaphorical cliff, while we stand uncomfortably holding all these atomic bombs.

We don't have a melody to sing, and John Adams music in Doctor Atomic is quite poignant for its lack of typical melodic and verse structure. It is frantic and anxious. On the other hand, he and Peter Sellars mine our history for lyrics, taking sonnets and mythology, biblical and other textual allusions along with historical records and scientific documents.

And it certainly does not let us go without breathtaking musical moments. The end of the third scene of Act I, with Oppenheimer singing his most memorable part, composed of the text of John Donne's "Batter my heart, three-person'd god", is nothing short of incredible in my mind.

Again, I know very little about the music. But the words say everything in my mind. The three-person'd god is the Trinity, the namesake for the test site, and the pattern of Western worship for the past two thousand years. But as John Donne prays to the salvation half of the god head while recognizing his affinity for the destructive side, and while Oppenheimer, our archetypical character of the news gods of the Atomic age, sings with visible pain of the powers of destruction and creation coming together within in his own hands, we see a new three-person'd god rising. The destruction, the creation, and the man unite into the imagination, the physical world, and the realization of the unity of both in human existence.

The opera ends in near silence--no explosion. The fate is what it is, and we all knows what happens. As the lights fade, a Japanese voice asks, fading as well, for water.

No comments:

Post a Comment