2/14/2010

Atemporality Onward and Always Inward

Bruce Sterling gave a keynote last week (or thereabouts, I mean, it is atemporality, right?) which was the sort of the coming out party for atemporality. I've been tracking the Twitter search on #atemporality for some time now, "listening to the aethers", so to speak. It was mostly Bruce, after the initial minting (or, thereabouts) of the concept by William Gibson a while back, with me and a few others throwing in every now and again. And of course the retweets, trickling down through the matrix like drops of condensation on a window. But now atemporality seems to have blossomed, with a mushrooming of traffic, and several new original contributors picking up the hash tag with new links, etc.

It's atemporality in action!

As I was discussing with M earlier this evening, this is a term that's philosophical time has come. It's a natural extension of several things going on in philosophy, history, and other relevant disciplines. After the end of grand narratives and post-modernism, we need a place to pick up the narratives that remain. Atemporality is simply a coined term for the various technological phenomena we're currently witnessing as our semiotics continue to transform themselves. It's an extension of the resurgence of interest in Bergsonian time, and the investigations of Foucauldian information and technological theory in the age of the Internet, and the aesthetic applications of Deluzian thought regarding desire, society, and information by the next generation of information theorists, and a philosophical grafitti technique being wielded by the post-Burroughs and ex-Dadaists, and estoterics, and occultists, and artists, and writers, all looking for the next new thing, and trying to find something a bit more concrete to explain what the hell we're all doing on the Internet all day long.

And other stuff too.

Of course, the thing about a new, interesting concept like this, is that it can all of a sudden be everything, and we can draw diagrams of the microcosmic and macrocosmic universes from an atemporal angle, play atemporal samples in our DJ sets, and cook atemporal pizzas. Or it can be nothing, and just be a flash in the pan Internet meme.

Well, its all in the usage really, and we'll have to wait and see. Meanwhile, I think it can bear some fruit in various guises, (especially in the atemporal pizza category). There are more than a couple academic disciplines that could use a new buzz word to play with too, and might even get some good work out of it.

But where it really gets interesting, I believe, is when we push the concept. So, now that the term might start being deployed, we shouldn't just add it to our jargon tool box, and take it out on weekends to parties. It is time to take it out on the road, and see exactly what this baby can do.

From my perspective, it's not just the next buzzword. All of those philosophical names I dropped a couple paragraphs up are stuff I've been working with for about five years now, and trying to pick up the wires, test the connections, and figure out where they lead. I'm a bit invested in the concept from a metaphysical and semiotic philosophy perspective, and I think it could really be the ground of some heavy work, if I ever get back into the philosophy game seriously. In the meantime, it is some heady stuff, man, and it's freaking me out.

Of course, not everyone will use the word like that, or maybe no one will be me. But still, I think there are some experiments we could all try at home.

For instance, I had this idea about the mail recently. Atemporality? Well, not strictly about time. But what we're starting to realize, as more and more people read and listen to the idea of something so formerly concrete as TIME and then say to themselves, "hey, there might be something to that" is that the things we thought were concrete, level, and plateau-like might actually be as flat and hard as the surface of the ocean. Which is hard, when smacking it after a large fall, but is also easy to penetrate if you know how to do it, has currents of its own, and also, also sorts of crazy creatures living in an ecosystem beneath it, totally invisible to someone about to drop onto it from a few thousand feet. Not that the mail has creatures living in it, but the fact is, it is much more than simply sending a letter from one place to the other. It is a massive infrastructural force, employing a large number of people spread across an entire continent, able to do amazing feats of physical transport, wasted almost completely on sending junk mail. So what is the postal system, really? What could it do? What if we re-envisioned it in light of our current technology, and the current way we are learning how to use our current technology? What might happen then? Well, it might be a stunt, or it might make something new and really useful. It's hard to say.

What else can be re-envision? What, pray tell, after our metaphysical and conscious assessments of the fabric of time itself, could we think of in a new light? And is it just a re-evaluation? A new perspective? It is not just a new look, more of the same look, with a new ruler. Or measuring, without using a ruler at all. Measuring something that does not require space, or quantify in such units. It is not a new perspective, so much as all of a sudden being able to see multiple perspectives at once. To look towards the future and back at the past with the same feet that are currently standing in the present. An extension of a point in time, a leaking of nowness, into and through always and forever. Singularity in terms of entirety, and multiplicity in terms of universality.

Sure, it sounds out there. But there are two sorts of infinite, that of the very large, and that of the very small. And in this case, while the universe at large and quantum physics might be an interesting place to look, I'm more particularly interested in those things that we think are important, such as time, space, technology and philosophy (big things) and those we are willing to overlook, like literature, numerology, folk songs, music video dance moves, the sorts of paper we write on, the words we still won't say in public, what objects vandals select to break windows with, and the verb tenses in poorly written street graffiti (little things). This is not pulling atemporal rabbits out of every hat, finding examples of the meta theory in every little cultural studies scrap and crumb. It is finding the new things. Who has done things in the name of atemporality? Who has thrown a brick with the word "atemporality" written on it? Anyone? What if they did? What sorts of paper support the sorts of atemporal writing that we already have been doing and will continue to change the way that we are doing in an atemporal way?

We are not looking for old artifacts of atemporality, or proposing new atemporality research. The whole idea is that what we are looking at when we are looking at atemporality is exactly what we're already looking at. Atemporality is not something new we're figuring out and we're trying, it is what we're always already doing. It is seamless with seamlessness, and continuous with continuousness. It is outside the old strata of time with starts and stops, with beginnings and ends. Therefore, it is outside outsidedness. It is inside insidedness. It is not irony, but the conditions under which anything could be ironic. And in this sense it's the same as it's always been. Except that things now are different. Irony doesn't mean the same thing as it used to. It never does. It never did. The meaning of things is always changing. The meaning of meaning is always changing.

So let's keep looking after it. Anything atemporal going on, make sure to report it to the usual non-authorities. Take pictures, if you can, and geotag them. Hashtag them. Upload them anonymously to sites with no links that will only retweet them six months later. If you find any evidence of anything, sequester it, buy space on a throw-away for-profit satellite, and fire that sucker into orbit. Feed it to a giant squid, and upload the video of the squid on YouTube, and then put the squid in orbit. Blog it all, and then force Google to delete your blog, and then tweet about it until it comes back. Echoes are everywhere. Try to drown them out with new noise. Events have not been planned.

Can someone crowd-source me the mailing address to send for an automatic digital atemporal pizza delivery? No? Well, let's keep looking until we can.

12/22/2009

Publishing Dialects and Dialectics

The eminent Bruce Sterling has written a foreword to a new publication of Zamyatin's We. Not the most interesting publishing event of recent memory, perhaps. But, it's a great book, a classic, one might say. I first read it for a course my first-year of college about concepts of freedom and power. I can't remember what the name of the course was, but I very much remember the book. I love how the main character has a changing relationship to the hair on his arms. I think about this all the time, especially when I'm writing about the body.

So, I'd like to see what Mssr. Sterling has to say about the book. He's been named one of the most visionary and interesting SF writers of our day by any number of visionary and interesting sources, so maybe he has something interesting to say as a prelude to the reading experience of We, a very visionary and interesting book, which in its own way is a foreword to the interestingly visionary genre of SF writing.

So it's been decided. I should definitely read this foreword.

But wait a minute: it's not on the Internet.

I know--one wonders if it is a hoax, because a critically-interesting essay by Bruce Sterling is not available on the Internet. How can we be sure the foreword actually exists? Sure, it's mentioned in an Amazon listing, but lots of fake stuff ends up on Amazon. I guess I could go down to the local book store and buy the book. But I already own a copy of the book, it just doesn't have the foreword. I suppose I could upgrade, but $10 is a lot of money to pay just for the foreword. And plus, then I'd have to carry around duplicate pages I don't need, unless I ripped out the foreword pages and glued them to my copy. I could give my old copy to a library or a friend, but it has all my class notes in the margins, which I want to keep. And plus, it's all dog-eared from use.

You know, this reminds me of a similar situation.

The similar situation is my experience with Adobe's Creative Suite, made by perhaps one of the most neurotically anal retentive Intellectual Property controllers in the world. At work, I have the original version of CS. I know, right? Well, it still works, and it cost a damn pretty penny to buy in the first place A WHOLE EPOCHAL SIX YEARS AGO so my employer is not going to upgrade my work station to the current version, which because they are now up to version 4, would mean buying the new software outright. Meanwhile, while I can work fine on my own computer, all the files that customers send me, created with CS versions 2 through 4, are as completely useless to me as if I had no top-of-the-line graphics editing software at all. I am cut out of the graphics editing community, which as anyone in this community will tell you, is tantamount to being able to work with graphics at all. Artists gotta talk to layout, who gotta talk to publishing, who gotta talk to prepress, who gotta talk to press. Me and my poor CS1 are an island on this tempestuous sea.

So what is the connection here? Besides the fact that I'm poor, and totally behind the current wave of publishing?

The connection, my Internet friends, is the nouned adjective of "Canon". Canonicalness. The state of being akin to the canon.

Zamyatin's book, in addition to being a wonderful element of the human literary record, is in the public domain. [CORRECTION: it is NOT in the public domain, because the copyright was renewed in 1954 by the translator! I can't find info for the original Russian copyright status. Translating throws a wrinkle on the wrinkle, so instead of altering my argument, I'm leaving it how it is, and will let you interpret this additional conundrum of translation yourself. The actual status of Zamyatin's book is not my argument.] The copyright is null and void, because it was written so many years ago. There are various, complicated rules for exactly how a book enters the public domain in various territories and jurisdictions, but basically, it was published so long ago that we as a society have determined that the right of the author to sell the book for cold hard cash has lapsed, and now the book belongs to all of us, or more properly, whomever decides to spend the money printing the words onto paper. The Intellectual Property aspect of the work has joined the idealized world of the literary canon, from which aetherous realm it can be channelled by any press-savvy patron of the arts, and delivered into mine hands.

So, if a work is free, and anyone could potentially download it on the Internet, why would a publisher bother reprinting a new edition, especially when another publisher could do the same thing? Well, there are several reasons. One, is because people still like reading paper books, surprisingly enough! Another is that they might remarket the book for new audiences, or for particular markets, say, on the 75th anniversary of the book. Often for anniversaries, they will remake the book as well, in a special edition with new translations, extra critical material, and really sweet new cover designs. In this particular edition we are discussing, Bruce Sterling's foreword is the new part. Oh, the cover is new too. I'm willing to bet that Creative Suite had more than a small part in the cover design.

But the part of the book that is in the public domain does not include this new material. Bruce Sterling no doubt retains the rights to his foreword, no matter what it is published afore. You cannot reprint the edition of the book precisely, because the design is owned by the publisher. Only the text is canonical, and only this text is in the public domain. We, the literary society, does not own the extra features. We only own the nebulous, ideal, (and strangely, valueless) part of the "work", not the actual book itself. The mind belongs to us, but the body is sold by the publisher.

One might say that this same mind-body philosophy dictates Adobe's view of software. We do not own the Creative Suite itself, or any claim to the power of the program that allows such wonderful graphic editing. We own a license to one particular version of the programming, to use this programming up to the limits of its purposeful publishing in this manner. We own the "printed pages", but the aethereal, ideal qualities of the software is Adobe's trade secret.

In software, as far as I know, there is no public domain. First of all, usable software is pretty much less than fifteen years old. Second, there is the thing called "source code", which drastically separates the usable features from the programming that actually makes it work. A metaphor to a book could be a text that you are not allowed to read, but only allowed to listen to someone else read aloud. Of course, back in the day, all text was read aloud, and remembered, so if you heard a story, you could read it and publish it as well. Programs used to be only "source code", too.

But the point isn't simply about establishing a metaphor. The point is about what it means to establish a philosophy of the relations between authors, publishers, and readers.

Some in the software world view Adobe and other software companies' philosophical position as draconian, and untenable. These "some" prefer to set up different philosophies, such as the GNU public license, and other metaphors, like the "free-as-in-beer" philosophy. Some of these variations are probably the closest software gets to the public domain. Not only are you allowed to use the software, and distribute it as is, you can change it, repackage it, and sell it, if you want. Certain licenses mean that the free aspects have to remain free, no matter how you package it. But in the most free varieties, you can do anything you want. It's yours, and you have no responsibility to anyone else in your use. I've heard the programming described like a spoken language--if you hear somebody say something, you can repeat that language however you like, because this is part of being a free individual. You are responsible for your own use of language, and nobody can impose proscriptions on your speech.

Now, with the caveat that I've probably crossed a bunch of categories in the world of open source software licensing with this last paragraph, let me say that a book is still different. Programming language is similar to written language, and yet different. Firstly, from a pure semiotic standpoint, programming language is a written language (mostly English and general Math-speak), with syntactical variations to allow easy logical functions, and then also codified so that it can be parsed into binary, which is the written language a computer understands. So a programming language is not a language per se (ha!), but local dialect, meant to convey a certain sort of meaning in a localized framework, i.e. the programming and parsing relationship between programmer and computer. So, source code, the "body" of a program, is not actually a proprietary language from a semiotic point of view, any more than a computer kernel is the "brain". In fact, both are textual works, written in a unique language that can be expressed by a computer and programmer alike. But without the technology, the computer, in the middle to transcribe and "read aloud" this special text, the book is unusable. When the computer and the user both read the same language at the same time from their individual perspectives, amazing things happen. This sounds a lot like magic for a reason.

But these program books only seem different, because thus far we've only considered the side of books that are written. We've discussed the programming, but not the parsing and program execution. Naturally, the author has a feeling of filial implications for his/her work. "I made this; it belongs to me." Sure, to an extent. But remember, the reader is involved as well. Without the reader, your novel just becomes a very strange, third-person fantasy diary. The technology by which the reader parses the text must be part of this relationship.

So what about the reader? Well, back in the day, the reader had to make a choice. That is, s/he had to choose to buy a book, and stick with that decision. If you wanted to have a bound copy of words all to your very own, you had to pay somebody to put them there, because books didn't grow on paper. Fair enough for free market philosophy. Of course, the publishing industry was willing to work with the consumer on this. Most people didn't have enough money to buy a new hard-back encyclopedia every year. So, we got cheap paperbacks. Dime novels--an entire genre of fiction based around a particular sandbar in the massive river delta of supply/demand curves. Serials. Pulp. There are certain ways people would buy books, and so, wouldn't you know it, people starting making these particular books. Publishers even began to support the ultimate non-consumerist, socialist revolution in literature--free, public lending libraries--because if literacy was universal, they would still sell a hell of a lot of copies, because not everyone could read the same book all the time. Besides, libraries were a good market for hard-bound copies.

You see, books are in their own way a particular local dilect(ic), (hey! who put that parenthetical there? this isn't a marxist concept!) that communicates between the author and the reader. Publishers, out of necessity, have been the mediator of this. They sell the computers, I mean, the technology, I mean, the books. You might have noticed Adobe gets along pretty well with Apple. That's because Adobe wouldn't be able to sell so much graphics editing software, if there weren't shiny new MacBookPro's just itching to run the software. The necessary technology for forming the semiotic/mechanic dialectic between two material points in a productive relationship functions as a part of the whole. The particular iteration of language used in the process is developed by and for the communicative relationship, always already part of the process. It is not so much a mind and a body developed in Cartesian dual-unity, as a Bergsonian echo of duration between phenomenologically linked network nodes. Shifting back and forth, the sand is already going to be forming a river delta...

Sorry, got carried away. Let's get back to today. In the past, books were published in these ways... etc. But what about today? Does technology require me to purchase a new copy of a book I already own, simply because my curiosity and investment in this particular node within the canon of literature pushes me to want to read Bruce Sterling's foreword to a historical proto-SF novel? Is this the current state of reading technology? Am I so obscure in my interests to be a specialist, or a collector, or some other fetishistic anomaly that would cause me to overbuy this particular literary-material language group, like someone buying a supercomputer to analyze the human genotype, or a collector desperately trying to find a working Atari to play the original Asteroids cartridge? Am I a polyglot by need, or simply because I want to be? Why would I dedicate myself towards communicating in the multiple languages of both "New Canonical Release" and "Old, Dog-Eared Text", basically to communicate the same thing?

This is the era of the iterative web app, of atemporal Internet usage, and of crowd-sourced wikis. I think we can do better than having to make a choice between A and B.

We, the expressively speaking/writing/reading culture of humanity, is very quickly getting used to a new way of communicating. Our nodes of communication are proliferating very rapidly. We are now developing new idioms and syntaxes based completely around the ability to transmit idioms and syntaxes quickly and succinctly. Our technology is engendering new technologies. Our programming languages now form carefully considered Graphical-User-Interfaces, which communicate through meta-data messaging services alive on a hyper-fast, always-on protocol networks, these Interfaces competing to write their own logical search algorithms, tracking the latest in spontaneous cultural generation of slang and communicative semiotic gestures, whether acute or obtuse, as long as they are usable enough to carry meaning within them, among as many people as we can still process a continued conversation, using all of these language tools. Yeah, I just described Twitter's Trending Topics. 140 characters never sounded quite so big, did it?

So the canon is growing, and even more so, canonicalness is growing. Comments, crowd-sourced translations, linkbacks, live search, hashtags. Some of this new communication is important, and some of it is not. But how can you tell what's important, without having some way to access it? Maybe Bruce Sterling's foreword is less than 400 words, and is just some glowing name-check to the idea of SF under totalitarianism. Maybe I don't need to read it at all. But how do I know that? I've followed the link, and come to a dead end. Maybe I click through it in under twenty seconds, but if access is denied, how will I ever know? The canon is shooting itself in the foot. Publishers could not, at one point in history, have said, "well, once universal literacy happens, then we'll start thinking about changing our publishing strategy." A growing canon is an ecosystem. It doesn't simply track a curve, or a timeline to decide the public domain. If somebody wants to join the canon, if somebody has something important to say, they must put it with the canon. And the canon, the realm of the literary, where linguistic worth is not so much a nebulous idea as it is a ever-present, living, conversation in mutated dialect, is something that is shared, and networked. It always has been, and always will. All that's changed is that it no longer needs paper. If one piece of technology changes, then the way we communicate in a language previously dependent on that piece of technology changes, even as we continue to use that technology. You can still own a landline, but you better believe you're going to be calling people on cellphones. I'm not looking for an updated ebook here. I want to read Bruce's foreword on pages, in a book, as a preface to Zamyatin's We, in the same edition I read in college, will all my notes still there. Is that an insane request? Maybe a few years ago. But I'm posting this idea on a cumulative public diary stored on a computer I have never seen, with a public network address, written in syndicated meta-language across any number of syntax parsing programs, updateable instantly from any terminal attached to the same global network. Don't you get it? Blogs ARE insane! You try to tell me what technology is insane. The mind/body distinction is not just dissolved, it's scratching it's head in Intellectual Property court, stymied by legitimately elected political parties comprised of people under thirty. The insanity of the real semiotic mechanisms of human communication are not just some wacky internet theory--they actually are the Internet.

I don't expect publishers to understand. Most of them have their only speaking language in the dialectic of profit, which has been a popular idiom for a while now. However, as ubiquitous as the capitalist language is, and however deeply in conversation it may be with our other technological languages of production, consumption, and communication, "the ability to make money off of something is the tautological reason for its existence" is a relatively new work of literature. Capitalism may be a fact, but it isn't the prime cause of our communicative culture. So, while meanwhile, publishers do such things as DELETE EVERY COPY OF 1984 OFF OF ALL KINDLES WORLDWIDE, in another one of those "I-can't-believe-it's-not-a-parable" moments, I have no doubt that I will one day hold an iterative paperback book in my hands. And even if not that precisely, something else that represents ability of the literary canon, which after all, is no more than the vast tide of cultural communicative forces circulating around a collection of particular nodes, to adapt to the speakers of its collection of dialects and idioms. I can't predict the future. Maybe in some years, nobody will even read Zamyatin anymore. Maybe I won't either. But regardless of the subject matter, language will continue to express itself between creators and consumers, finding new ways to do so, and adopting new languages of expression as they become available. Because this is what communication does. The saw "information wants to be free/expensive" is stuck in the capitalist language. What it should say, and what is the most true tautology of them all, because it DEFINES tautology, is that "communications communicate". They don't want anything, but by sheer fact of their existence, they do what they do. Regardless of through what technology you choose to express communication, it will seek to communicate, or it will fizzle, and other communication will take its place. Just try to make the human race shut up. The amazing part is, through all the noise, little by little we slowly start to make more sense.

Meanwhile, my version of CS still has Adobe's stranglehold all over it. Guess we're lucky that there's more than one slick standard for distopian, proto-SF novels out there. Adobe brings you the new cutting edge standard in SF--Jules Verne, version 2375! Now upgrade from version 2374, only $499! Limited time offer!

11/24/2009

They didn't have video in the 18th century, okay, pal?

JL: I recall hearing you talk to Steve Jackson about electronic books. You said you thought that they were just throwaways.

BS: Yeah, software is throwaways. Where is your Apple software right now? Where is your IIe software? Do you even know where it is? You know how much money you sank into that shit? What can you do with it now? Zilch. Nothing. People just don’t keep that s tuff the way that they keep books. It’s profoundly disposable. I’m not worried for the future of literacy, though. Some people think that nobody’s going to read books in the future. I think that’s ridiculous. You can learn stuff from books that you can’t get from video, period. For one thing, without books you’re not going to know anything about the past 5,000 years of history. They didn’t have video in the 18th century, okay, pal? And if you want to know anything about the 18th century and what went on i n it, say, why the American republic was started and what people meant when they wrote the constitution, you gotta know about books. You’re not going to get that out of a Hypercard stack, I’m sorry. And if you know that, you’re going to have something ver y valuable…not just culturally and artistically valuable, but practically valuable. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance. If you put a guy with 800 channels of tv next to a guy who knows how to go to a library and do serious research, there’s no ques tion who’s gonna know the skinny…

10/14/2009

Get Weird, Young Man

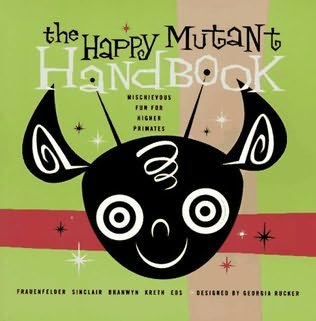

The book is, The Happy Mutant Handbook, made in 1995 by Mark Frauenfelder, Carla Sinclair, and some of the other original boingboing crew. Basically, it's a handbook into the lifestyle of the typical boingboing enthusiast, filled with essays, bios of interesting people and groups, a few manifestos, and lists of resources accessible through something they keep calling "the Net". Whatever that is.

The book is, The Happy Mutant Handbook, made in 1995 by Mark Frauenfelder, Carla Sinclair, and some of the other original boingboing crew. Basically, it's a handbook into the lifestyle of the typical boingboing enthusiast, filled with essays, bios of interesting people and groups, a few manifestos, and lists of resources accessible through something they keep calling "the Net". Whatever that is.Now, I give boingboing a little bit of crap now and then, simply because now it is popular, and almost, like, mainstream, so they get to lead the flying-V of geese for a while, and get hit with the worst air resistance. Sure, I lamprey a few links from the mega-feed now and then without citing my source. That's what the big shark is there for! But really, this book in no small way made me the man I am today, and that's why I want to talk about it.

Let me set the scene for you a little bit. The year was 1995. I was in seventh grade. The year before I had just moved back to the US after living in Germany for two years, moving into a suburban wet dream in Connecticut. I was extraordinarily introverted; I had always been a bit of a "entertain myself" kid, though social enough, but upon coming back to the States to realize everybody had made ultra-serious friendships in 4th and 5th grade and become obsessed with all kinds of music I had never heard before and talked constantly about something called "Saved by the Bell", and that my shorts were way too short... well, let's just say it drove me a little inward.

Looking back on it now, I really fear for that poor thirteen year old. He might have met a horrible fate in suburban Connecticut. He might have watched a lot of TV, kind of liked the Gin Blossoms, and went to school for business or actuarial training and settled down in a similar sort of suburb, maybe finally getting married and producing spawn. Or worse, I could have been driven inward, and worn all black, and had a really bad attitude, and maybe grumbled to myself while I drove a bus. Sometimes I think we forget just how much teenagers need affirmation. They desperately need someone to tell them they are okay, that what they look like and what they say and do is not horrible. West Hartford, Connecticut was not going to tell me these things. Hell, I didn't even play travel soccer. Of course, my parents thought it was fine that I told weird jokes and read a lot of books, but being a teenager means that your parents' affection all of sudden is no longer enough.

And this sob story might have continued, if I didn't lurk around the magazine racks at Barnes and Noble, which was just about the weirdest place in town after the hobby shop, after the record store closed so a greeting card store could open. In the back of the racks, behind the legitimate glossy magazines, I found odd-shaped magazines about computers and music, and weird stuff like esoteric religions. I always wondered how these magazines survived, if nobody had ever heard of them. I was interested in the Internet, and spent a lot of time exploring BBSes. I kind of put two and two together, thinking that maybe these weird magazines were sort of like the Internet--something almost free, not really for money, that only a few people knew about. I bought copies of 2600 and Z magazine, and understood almost none of it, but enjoyed the tiny 8.5 x 5.5 shape, and the feeling of reading something edgy nobody knew about or understood. It was arcana for me, and I would just like holding it in my hand, the way kids carry Animal Farm, or the Communist Manifesto. Just to feel those edgy words in your hand.

I never found bOINGbOING, the zine. This was still West Hartford, and the Barnes and Noble. I have no idea what 2600 was doing there. Maybe it was well known at that point. I didn't read any zines (unless you count 2600), and I wouldn't for another five years. It wasn't until the Internet really took off that I even understood that you could get zines, and they weren't just given to you by somebody you knew, on the sly, like underneath a diner table or something. But I didn't have any money anyway, so it didn't really matter.

What I did find was The Happy Mutant Handbook. Like all zany guidebooks, I was charmed by its unassuming and calming cover of a smiley mutant with big ears and antennae. Picking it up and flipping through it, I saw a bunch of things I didn't recognize, but stopped for the hilarious list of posts from alt.shenanigans. I saw articles with things that looked like instructions, but for... concepts? I saw a little bit of media hacking; I knew I liked that.

I don't remember if I read the "What is a Happy Mutant" section there at the store or when I got the book home, but I knew instantly that it was addressed to me. It told me everything that I needed. It was like someone had translated a first-year sociology text on counter-culture into my vernacular, and put a lovely "go! do it!" spin on it. I needed little more prodding than that.

I read the whole thing cover to cover. I still remember the sections on The Church of the Sub-Genius, and ribofunk. I sent away $3 for a pack of Schwa stickers. I looked every http and ftp address they printed in the guide, checking them off in pencil when I had. (I didn't follow the AOL keywords, being a Compuserve kid, and I didn't know how to make gopher work. Ha! 1995!) I signed onto the Usenet for the first time, and printed out pages and pages of alt.shenanigans which me and my new friends read to each other, cracking ourselves up by acting out the scenarios. Yes, I was making friends, finally finding the other kids who liked weird and funny and gross stuff like I did. (The tears better be flowing down all of your cheeks.)

I pocketed other items into my brain for later. Cyberpunk, and confrontational art, and maker projects, and bios of counter-culture freaks, and tales of adventures of all sorts. I let my eyes drift over references to people and music I had never heard of and would not hear of again until much later. Two years later when I tried pot for the first time, and a year after that when I first consumed my first dose of magic mushrooms, still having no idea what my brain was in for, I felt no fear. I always wondered why I didn't have a hesitation when I accepted my friend's offer of schrooms. I've never been a huge risk taker--don't get my kicks that way. Tonight, reading through the HMH I realize that the bio of Timothy Leary played no small part in the evolution of my mindset. Mark Frauenfelder writes with no hesitation or caution about Leary's expansion of the mind with psychedelics. I trusted this book, and if it told me that drugs could be a not-bad thing, then hell, I would find out for myself. (Hear that, Mark? You made kids use drugs!) Of course, it wasn't alone in pushing me in this direction. Meeting people who do drugs who are totally normal is the best anti-anti drug ad you could imagine.

In the years since the book has been on my shelf, traveling with me across the country as one of my most treasured books. I might not have opened it in ten years before tonight, and I forgot a lot of stuff in it, having to discover it from other sources further on down the line. Hell, I never knew Bruce Sterling wrote the introduction! I didn't read Bruce's books until college, by way of William Gibson, by way of druggy SF cronies. And look at some of these other contributors: R.U. Sirius, Rudy Rucker, Richard Kadrey, and others. I didn't re-discover all these folks until the last few years. But with the HMH, things definitely altered direction for me. There were a lot of tangents, and a lot of detours.

From the logo re-purposing section, I first picked up Adbusters around 1998. While it didn't have the mutated illustrations I hoped for, it opened me to anti-globalism and left politics I could understand, before I read the heavy stuff. By turning me on to Usenet, I got onto rec.music.phish. You laugh, (and I laugh too) but this was my introduction to interacting with "real adults" as an equal over the Internet. Plus, Phish became my resident counter-culture for 3+ years, introducing me to all kinds of underground music and underground personalities, the history of counter-cultures itself, and of course, mind expansion via brain chemistry hacking. From there it was another short leap to electronic music, and underground literature, and to mystical and bizarre religion, and anarchism, and, well, the list goes on.

Being a newbie is one of the most important points in any enthusiasts career. Every community, or pursuit, or craft, or subject needs one hell of an FAQ. It needs to be tongue-in-cheek, and self-deprecating, and welcoming, and exciting. And of course, well-written. There's not always a teacher around, or someone to copy, so you need a source to give you the dirt. And well, HMH was my first FAQ on how to not be a douche bag.

Of course, I might have ended up in a similar place. Even a lot of the things I forgot I found elsewhere, and it would be hard to say if I hadn't stumbled onto this book I wouldn't have stumbled on to something else. But wandering around those cold middle school and high school halls filled with the walking corpses of J. Crew and Abercrombie, it sure was nice to have that book under my arm. I remember my friends and I sitting around, dreaming about driving a van across the country to the desert for Burning Man. We never went, but it was nice to have some sort of crazed mecca like that to think about. Out west, away from New England and the East Coast, there was a place where they burned giant robots and took drugs and drove motorcycles naked in the desert. The HMH was a revealed text to these kinds of crazy worlds, which we hoped one day to set off towards, as if we were going on a crusade, a crusade against the country we wanted to leave behind. It was like an ancient text, but from the future, showing us all this knowledge that we didn't know had existed in the past, but we might live to see it in the future.

So I eventually did go west, and then back east, and then west again, and went to college a couples times, and ate a lot of things I probably shouldn't have, and saw some awesomely bad bands, and read a lot of books, and read a lot on the internet. All in all, I've never had to look back with regret. It's pretty damn good, knowing you can make your life as crazy as you want to at any time, any where you are, no matter who you're with. I don't know if I'm still a Happy Mutant or not, but whatever the hell I am, it's pretty alright most of the time. Cheers!

And so to conclude:

Thanks Happy Mutant Handbook! You pushed me towards loud music, weird clothes, esoteric internet drugs, and no doubt reduced my washing frequency! I couldn't have done it without ya!

It looks like the book is unfortunately out of print, though there are used copies for sale online. I'd like the authors to post it online, in its entirely. Man, look at this world! There are tons of kids who need something like this to turn them on, and I'm afraid the Kindle just isn't going to cut it.

4/24/2009

The Poverty of National Calling Plans

The small-scale buzz around Bruce Sterling's SXSWi talk is pretty amusing, mostly because as he put it, "this offhand speech of mine -- truly a rant, delivered from notes -- is provoking a remarkable response specifically BECAUSE there is no crisp digital record of exactly what I was saying."

The small-scale buzz around Bruce Sterling's SXSWi talk is pretty amusing, mostly because as he put it, "this offhand speech of mine -- truly a rant, delivered from notes -- is provoking a remarkable response specifically BECAUSE there is no crisp digital record of exactly what I was saying."I love this sort of stuff (even when it doesn't involve shadowy Internet well-knowns). Literature is archaeology, man. And it's like we're digging through a city (well, maybe a hamlet) wiped clean by the sandstorms only a month ago. Is that a toothbrush? Maybe it's a shamanic scepter! Nah, maybe just a toothbrush.

But as our French Philosopher Phriends would remind us, the archaeology of truth is the sandstorm itself. None of this theology of the book! It's the Internet, after all. We all love the fact that it's okay that we make it up as we go along.

I'm pretty good at the making stuff up part. I have a degree in philosophy. The rule of philosophical scholarship is that you can make a dead guy say anything you want--you just have to manipulate the puppet strings. These puppet strings can be quotes taken almost of of context, the abstracts of papers somebody else wrote about someone else, or if you're of Zizek-stature (or first-year undergraduate) the mere name-drop may suffice.

Unfortunately, I also have these interests in stuff. Stuff makes me think. This means I can't quarantine my bullshit into academic papers alone--unfortunately for me, these reinterpretations, quotations, appropriations, and exhaltations are constantly circulating in my head, driving me slowly, but surely, to a state of being entirely boring. Unfortunately for you, I have a blog, which you seem to be reading. Hmm. I wonder what will happen next...

So, let's play the game.

WHAT DID BRUCE STERLING REALLY MEAN WHEN HE SAID THOSE THINGS?

What did he say anyway? Well, no one really knows for sure (this is going to be so easy).

Always start with the text.

"The clearest symbol of poverty is dependence on ‘connections’ like the Internet, Skype and texting. ‘Poor folk love their cellphones!’ (Sterling) said.”

"connectivity will be an indicator of poverty rather than an indicator of wealth," (note taken by Rohde).

The internet is poverty? Cellphones are poverty? What is he saying? These things GO AGAINST EVERYTHING MY INTERNET MARKETER TOLD ME!!!

Here is some actual Sterling text. From his short story (architectural fiction, no less) "White Fungus":

"Cell phones are the emblems of poverty."

Interesting enough. Would probably make some liberal cell phone users nervous.

But look at this--"symbol of poverty", "indicator of poverty", "emblem of poverty". Are we noticing a trend here? Call the semioticians!

Also of note: the quote from "White Fungus" is placed, in its original context, with the phrase "computers are not sources of wealth."

So what do we have here? We have wealth and poverty opposed. We have "source" as a flow of wealth, whatever wealth might be. We have "connectivity" as a given, of some sort. We have poor people with cell phones. And we have symbols, emblems, and indicators.

Wealth and poverty, the meaning of which these statements seem to circulate, have different applications. They are material concepts, but social as well. Generally involving value, the value may flucuate. Are we talking about social value? Are we talking about material value? Or are we talking about material value derived from social value? Or the other way around? What sort of poverty do cell-phones represent, and of what sort of wealth are computers not the source? Who is poor, and who is rich as a result?

The Twitter-phobic Internet folk have interpreted the point as purely social in message, and therefore at root, idealistic. We spend a lot of time on our cell phones, and therefore the precious, bourgeois "free-time" in which we would otherwise pursue such worthwhile, humanistic goals such as good, honest fire-side conversation, staring whistfully at clouds, and playing polo, suffers as result. It is an ironic musing worthy of a minor scenario of the Odyssey: through our frantic attempts at universal communication, a female cell-phone beast eats our ears, eyes, and mouth. Odysseus sails away on a plank, born on the gentle breeze of Athena's brain waves, thankful he never signed up for the cursed free internet-service.

If anybody is losing anything of value, it's happening materially. Material, of course, extends into the consciousnesses and compound consciousnesses of people, in less than solid, i.e. symbolic forms. But just because we assume a loss of something that never existed, like "true, meaningful conversation", does not mean we can declare a robber. Because somebody kicked over your invisible dandelion wine is not a cause for blows. If you're not talking to other human beings in a meaningful way, that's your problem, buddy.

We've written up the Internet to be some grand form of communication. It certainly is a form of communication (by way of good old fashioned reading and writing) but how grand is it? Those singularity morons aside, what exactly do we expect from the Internet, and how has it either surpassed or fallen short of our goals? These sorts of material questions deserve attention. So put down that pen and paper, junior Thoreau. Turn up your headphones, and let's dance.

Communication, as a flow of symbols throughout our conscious perceptions of the world, are not strictly the material facts of life, but they are the way we understand them, as the capacities of our sentience dictates. In addition to providing a smooth flow of sensation in the way we would hope between the ideally closed confines of our mind and the cold, cold world, they also get a bit tangled in the intermedium, the interpretive membrane of flesh. Is what you feel what's really there? Is what's there what you really feel? How sure are you that you feel what you feel? In these tossing seas, in which there is no Ithika, there is as much agonism between every drop of water as there is undifferentiatedness in the silence of drowning. Don't worry, we're pretty good swimmers. And maybe the gods do exist; you never know.

So we can worry about the hubris of the "real world" at the same time as we kick and thrash in the liquid of our minds. But you best not forget strictly material world--or else you will find yourself floating face down. The interfaces between the worlds of consciousness and the hard rock that may in fact be out there is important, but only important when we have a bit of each in both hands. Think about the world, but also world about the think. Right? Right?

In other words, cell phones: what do they do for us, and how do they work? What they do for us only goes so far as we know how they do it. Otherwise we're just plugged into our own sensory feedback loop. There are clear benefits of communication that don't require a list. But how do they work?

Poorly. And I'm not just talking about signal strength. Look at the material models for our high-tech communication networks. It's full of "pay as you go" reverse indentured servitude, credit/fee contract scams, and monopolies. I pay over a hundred dollars in "connection fees" per month to stay networked in the way I find useful. WTF? That's more than my car insurance. I could set up my own telegraph station a hundred years ago for less, probably. What future is this?

Not to speak of the hardware itself. Dropped calls, bad operating systems, bricked phones on their way to the e-waste fields of China. App stores? Fart programs? Are we serious?

Materially, (in the strict sense), we are all slaves. When I build a transistor radio set, perhaps I'm connected. But with a cell phone, I've mortgaged my flow of information.

This is the ongoing rebuilding of the credit economy. Housing collapsed--wait for the information infrastructure. People can't pay their data bills, and drop off the network. The content begins to shrink. There is a rush to "flip" domain names, but nobody is reading anyway. Eventually, land lines shut down, or are taken over by the government because they the tubes are too big to fail. It's not dot-com VC sink holes, its the crash of information itself.

This is the ongoing rebuilding of the credit economy. Housing collapsed--wait for the information infrastructure. People can't pay their data bills, and drop off the network. The content begins to shrink. There is a rush to "flip" domain names, but nobody is reading anyway. Eventually, land lines shut down, or are taken over by the government because they the tubes are too big to fail. It's not dot-com VC sink holes, its the crash of information itself.So in a class sense, we are the texting, twittering, blogging poor, the proceeds of ill-gotten AdSense all being eaten by the Company to pay for our web hosting fees. If you advertise, you are basically sharecropping.

And I haven't even mentioned the fact that a cell phone will not make anything edible, does not cure a single disease, or reclaim a single molecule of CO2. All it does is call people! We'd be better off giving every person a good pocket knife than a RAZR.

Is ubiquitous connectivity useless then? A tool of the oppressing class to profit off our work, and nothing else? Should we burn the factories, and shove our clogs into Web 2.0?

Is there no benefit for the poor having cell phones? What about teenagers? I think it is safe to say there is a benefit. When I was trying to find an apartment and a job at the same time, with no mailing address or reliable internet connection, my cheap, free-with-contract cell phone was my only link to the material world. It was my access, and the only one I had--not to community or SMS, but to anything. Access is good--because then you can use it however you want and make it as utile as you wish, even if it is for mostly LOLing. In this world when few material things are concrete these days (think of rural Africa, where a cell phone connection is more likely than a water and sewage line) this shard of access is the only thing many can depend on--and we are rapidly re-organizing our material lives around this anchor. The problem is that we are kept poor by these anchors, because someone else is dolling out the rope.

The material use of a tool or object is a certain sort of value, and the control of that object, via less-material pathways such as "contracts", "property", and "debt" is another sort of value. I believe a bearded man other than myself wrote something about that once. Along with the rise of Access as a new axis in our material lives, other sorts of value appears, connected in different ways. There are various sorts of social value, with different amounts of relative worth.

For example, cell phones are status symbols, by which we judge relative wealth. Just like cars, before people decided they'd rather drive electric flat-screen TVs than new SUVs. The cell-phone is a commodity as well as a tool, and there are certain values of having a certain connectness; being able to say "you can always reach me on my blackberry" has a value in addition to anything that might be said in the email. And this is before you cover the damn thing in pink rhinestones.

But the act of communication, can be a commodity, as much as it is the use of a tool. Lots of people buy into the idea of communication more than they actually communicate. My Loyal Internet Marketers for one. (Yes, I have about twenty or so. They all follow me on Twitter. The best part is, they are just as useful whether I read them or not! And they are free! If one quits, s/he is replaced by two more!)

There is a certain idea of the Internet going around, one which you might be familiar with. It is a familiar story (though not perhaps as familiar as The Odyssey), and one much loved, especially in this country. It is a love story--Demos, our perennial hero, falls in love with Techne, and they decide to start a family. Because they believe their love is so perfect, they decide to adopt a child: Kratia. Kratia, unfortunately, is not a child, but a dark spirit from way back. Because of their love, Demos and Techne were blinded to the spells of Kratia, and did not see it in its true form. They thought, oh, its only a kid, give it a cell phone, and it will be fine. But then when the monthly bill came back...

We think that technology, somehow, is the final proof of democracy. We've merged our belief in the destiny of capitalism and freemarkets with our sleepy trust in democracy to maintain a fair balance of power. These two great tastes actually don't taste like anything together, but in fact continuing doing what they do best--democracy consolidates the power of the people into commodity leaders, away from the economy where it belongs; and technology continues to evolve like a tool, according to the actions of those who wield it.

As our economy gets more technologically rigorous, the powers that control the economy also control more technology. In the interest of maintaining this power, they use the tools they have at hand, lulling Demos to sleep with Techne's sweet songs.

Don't know those lullabys? Ever heard of American Idol? Vote early, vote often--the true democrat's popularity contest. How about the Obama SMS network? Feel connected? Feel like one of the people? Yes we can? How much do you get charged per text message?

The technology of the Internet has given democracy its return to populism, all right. You feel more like Demos when you're with Techne, don't you? You are so in love with her, you can't even remember who you were before. But don't blame Techne. She's under the spell too. It's the product of your love, that demon, bastard spawn that crawled off into the dark woods when you two were busy humming little love songs... Power... what gave birth to evil itself...

Anyway, that's enough with the stories. But wait, one more:

"The Internet — we used to call it a ‘commons’. Yet it was nothing like any earlier commons: in a true commons, people relate directly to one another, convivially, commensally. Whereas when they train themselves, alone, silently, on a screen, manifesting ideas and tools created and stored by others, they do not have to be social beings. They can owe the rest of the human race no bond of allegiance." - Sterling, in "White Fungus"

Did the true commons ever exist outside of the Arendtian notion of the agora, and those other high-minded Greeks and liberal humanists? Sure, we commune all the time. But humanity is not a commune--never was. There were always tools, people, and power. The relations shift around, but the players stay the same.

So what is worth? Where does the true value lie? Not in any particular person or tool, certainly. It's in the relationships between them. The pathways that guide certain people to use certain tools for certain goals. The path of a hammer to hit a nail; the text message to offer a friend a job; the processing of information to sort out a story--a story that might teach someone how to use a tool better. The objects, and even the people are mere symbols, emblems, and indicators of power and potential power. The symbols only have the value we give them, as we use them to mediate between ourselves and the world. Cellphones are emblems of our poverty. Computers don't make value (unless your desktop is at Moody's). And here we are, back in the beginning--people and symbols, symbols of people, people symbolizing tools, and tools symbolizing people.

Poverty--who is poor here? I suppose in the end, everyone with a cell-phone. They are the least common denomenator of Access these days. So we're all poor, in the respect of technology. Only some of us more than others, and and some of us, decidedly more materially than others. But maybe some day, a cheap, open-source free access to the networks will be devised... and then we can all be the salt of the earth. After looking at the bailout packages, I would rather we were all equally poor, frankly.

What does Bruce Sterling think? Hell if I know! Shit, that guy is crazy. Every read any of his stuff about global warming?

1/28/2009

I've been Sterlingged

370-some posts in one day was a pretty big bump for lil' old Interdome.

Also, he and Rudy Rucker have a new short story in Asimov's about the end of the world visualized through the perspectives of two hardcore bloggers in the not-so-distant-future. The story is great; those guys are awesome. Any blogger should get a kick out of it, even the not-SF-and-techno-jargon inclined.

Also, if you examine the chart above, you will notice that most of my hits from search engines are drawn to my pictures of "Greek animals". This has been, consistently, the biggest single draw to the site since I published that post back in 10/07. Again, the Internet is a weird thing.

1/15/2009

Designer Theory for Designers

The article is pretty simple: basically, they feel that discussion of design and design itself is complicated by the fact that it has trouble defining its intention. In order to melt this complication, they devise a rubric of the four fields of industrial design, as such:

Commercial Design (design intended to turn a marketable product)

Responsible Design (design motivated by altruistic concern for a typically un-marketable group)

Experimental Design (design that pushes the limits, trying unconventional methods and motivations for 'pure research', for lack of better term)

Discursive Design (design meant to "communicate", much as one expects the more confrontational forms of art to do)

They conceded that most projects will overlap, but these general categories will hold. That's all pretty straight-forward and reasonable. The purpose is that:

"understanding the design landscape through these four, simple categories—Commercial Design, Responsible Design, Experimental Design, and Discursive Design—will help the profession, our "consumers," and ourselves better understand design activity and ultimately its potential in an increasingly complex world of ideas and objects."

And they enumerate how in more detail than I will.

But it got me thinking (as I often do): why don't we look at writing this way?

Well, for starters, the four categories are all based upon the intention of the work. Writers, while certainly taking their own intentions into account when considering their work (wait, what?) also have other factors in mind. I think there is much more concern for the "Craft" itself.

One might argue that the Craft falls under experimental or discursive, the two artier of the categories. Which it does, but also it does not. Both the experimental and the discursive intentions of design view their work reflexively, in terms of what it does to/for other people. Some writing could be taken this way, especially writing that does break some sort of barrier or cross some sort of line. For example, any work of fiction that was the subject of an obscenity trial could be said to be both experimental and discursive, pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable and the definition of artistic literature by questioning current discursive definitions. But what about someone who simply writes in the style of Burroughs or Ginsberg, now that both texts are recognized as valuable contribution to literature? That really can't be said to be experimental, and its discursive value would not be much different than the discursive value of any other piece of writing.

Most writers, I believe, would choose to write in a particular style because it is what is appropriate for the work, and stimulates them to write it as such. Far be it from me to argue that writing has any intrinsic qualities or essential characteristics to itself--writing is nothing without a writer and a reader. In this way, intention, as a force from outside the writing itself, is an axis that pins the three together: writer, writing, and reader (even if the reader and the writer are the same person). So intention plays a role, but the relationships between intention and these three planetoids are more complex that an analysis of the post-design market as relates to the product. The realm of ideas, conversation, and morals are negotiated markets just as much as the world of consumer electronic sales, and hence, simple "intention" falls a bit short in description. Why does a product do well? Simply because it was intended to do so? Or why does it stimulate conversation, or push the envelope? Even in the non-commercial markets, currency, exchange value, and commodity have various, complicated roles to play outside of simple intention--you don't need me to tell you that. So there are many different markets interacting, adjusting values and the status of objects, in a densely complicated web that pretty much defies anyone's intention.

But are these end, consumer markets the only thing that defines the creation of the product? Any designer could tell you there is much more to it that that. Many factors go into the design and production of an object; from cost of raw materials, to equipment needed, to durability of the design in shipping. Most of these, in times such as these, are monetary based--but they don't have to be. Ergonomics is a selling point both on the product end and on the worker end--because I guess it turns out that safety is more affordable than accidents in the long term. But what about other things like enjoyment of the task for the worker, or harmonious installation of the factory in its neighborhood? Are these foolish notions, or interesting design problems?

But are these end, consumer markets the only thing that defines the creation of the product? Any designer could tell you there is much more to it that that. Many factors go into the design and production of an object; from cost of raw materials, to equipment needed, to durability of the design in shipping. Most of these, in times such as these, are monetary based--but they don't have to be. Ergonomics is a selling point both on the product end and on the worker end--because I guess it turns out that safety is more affordable than accidents in the long term. But what about other things like enjoyment of the task for the worker, or harmonious installation of the factory in its neighborhood? Are these foolish notions, or interesting design problems?For the writer, they certainly aren't foolish notions. While it is not necessary for a writer to enjoy what he writes, I can assure you that the writing will be much higher quality (by any measure) if s/he does. There was once a fancy term for all these design problems in production, called "means of production". For a lot of people, it is still an important concept, no matter what you call it.

So what have I proved? That writing is not intention-oriented, or that it is? The relations of production, whether or writing or manufacture, are certainly symbolic, physiological, and capitalist markets of their own, and rightly so. So perhaps it is that our intentional scope must only be broadened: intention not only extends from the designer through the product to the consumer, but must extend in a web in all directions, from the designer to the product, to the worker, to the factory, to the city, to the transit system, to the sewer system, to copper piping, and back again to toilet design.

But I think I was right originally: there is a lot more to writing (and design) than even the most complicated "intentions" can encompass. Intention, after all, is merely what we discover after the fact. Why did you use that drill as a hammer? Oh, I intended to save time. No, you were lazy--because if you had though about it, then you would have easily come to understand that using an expensive, electric tool as a blunt force object would break it, wasting lots more than just the time to get up and get the hammer. Or a better example--why did you sell bad mortgages? Because you intended to help people into homes. Bullshit: you were greedy, and didn't care whether the person filling out the application was a family, a developer with no capital, or a con-artist. And even saying that is giving you too much of the benefit of the intentional doubt--greedy wasn't what you felt at the time, it was simply what we call your actions afterward. The strange machinations that make design, or any other procedure succeed or fail only later can be labelled as "good intention". To return to design as an example, the iPhone is only an example of good design after the fact, because it made a lot of money. If it had not, then it would have been bad design. The list of things that should have many money but didn't is as long as the list of things that shouldn't make money but do.

In the actual process of writing, and I imagine, in any other creative endeavor, there is a moment where production clicks, both in the hands and in the mind. This is about as far from intention as we could get. An author doesn't intend a verb to signify action, anymore than he intends to write the next great American novel (well...) because it is only in doing so that a verb is a verb, as it is only after the novel is finished that it could be considered within history. Symbols, like objects and people, do not intend anything, they simply do things in relation to other things. This is no more intrinsic than it is intentional--the fact of meaning is, as the philosophers might say, "relative," and by this I mean relatively meaningless. The fact that meaning occurs is, for all intents and purposes (no pun intended) miraculous. By this I mean as good as un-caused, and also as important as an act of god. The reasons behind it are theological in scope, and while arguable, certainly not directly relevant in their real importance. Just to be clear: I don't mean that the meaning of words comes from another dimension or streaming in heavenly rays from the firmament, or otherwise spontaneously bursting into existence. If god turned Lot's wife into a pillar of salt, he must have done it somehow, but I doubt that Lot or Lot's wife gives a good goddamn how he did it.

Back to the point: despite the unconscious, miraculous machinations behind words (ah... hint, hint!) the author, in lining them up one word after the other across the page, is working with them as unintentional fragments, using his own consciousness and intention like a needle to sew them together. This is a little sharp bit of an axis, but hardly one piercing them altogether. There are many more important factors to the author (and likely his audience as well), such as things as esoteric as plot, voice, and characters. Of course, we intend all of this to be "good", so that the writing is "good". And we intend them to do various things amongst themselves, organizing little markets of our own in the text. But knowing this and intending it is hardly a lesson on how to write well, is it?

Can you teach creativity? Can you make a rubric of the different categories of creativity? Can you intend creativity? There are lots of other things you can do, but I don't think any of these work. Creativity is, in a way, the opposite of intention, and its partner. You may intend something going into production, or afterward, say that you had such an intention. You might do the same with creativity--hoping for it in the future, and attributing it to actions in the past. But the difference is that at the very moment of production, in the act of producing, creativity may occur, where as intention never will. You might realize creativity when it hits, or not until afterward. Maybe you will eventually deny it, though others laud you for it. But when words flow out of the mind to the hand, creativity is the force that guides them, and this is where intention can simply not go. Intention can aim and pull the trigger, but creativity is the bullet that will or will not hit the target. Because, in actuality, it is the target as well.

So in the end, I suppose my point is this: the authors of that article are absolutely right. By thinking and discussing the role of intention in design (or anything else for that matter) the practitioners and users thereof will likely benefit by guiding their practice and recognizing their own potential. However, we all wish and intend lots of things--I hope that this thinking and discussing doesn't end there.

But maybe after reading this, you will wish that it did!

11/11/2008

"The dead [painters] shall be buried in the earth’s deepest bowels [which are filled with paint]!"

Here goes:

Manifesto of the Futurist Painters (1910)

Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini

TO THE YOUNG ARTISTS OF ITALY!

The cry of rebellion which we utter associates our ideals with those of the Futurist poets. These ideals were not invented by some aesthetic clique. They are an expression of a violent desire which boils in the veins of every creative artist today.

We will fight with all our might the fanatical, senseless and snobbish religion of the past, a religion encouraged by the vicious existence of museums. We rebel against that spineless worshipping of old canvases, old statues and old bric-a-brac, against everything which is filthy and worm-ridden and corroded by time. We consider the habitual contempt for everything which is young, new and burning with life to be unjust and even criminal.

Comrades, we tell you now that the triumphant progress of science makes profound changes in humanity inevitable, changes which are hacking an abyss between those docile slaves of past tradition and us free moderns, who are confident in the radiant splendor of our future.

We are sickened by the foul laziness of artists, who, ever since the sixteenth century, have endlessly exploited the glories of the ancient Romans.

In the eyes of other countries, Italy is still a land of the dead, a vast Pompeii, whit with sepulchres. But Italy is being reborn. Its political resurgence will be followed by a cultural resurgence. In the land inhabited by the illiterate peasant, schools will be set up; in the land where doing nothing in the sun was the only available profession, millions of machines are already roaring; in the land where traditional aesthetics reigned supreme, new flights of artistic inspiration are emerging and dazzling the world with their brilliance.

Living art draws its life from the surrounding environment. Our forebears drew their artistic inspiration from a religious atmosphere which fed their souls; in the same way we must breathe in the tangible miracles of contemporary life—the iron network of speedy communications which envelops the earth, the transatlantic liners, the dreadnoughts, those marvelous flights which furrow our skies, the profound courage of our submarine navigators and the spasmodic struggle to conquer the unknown. How can we remain insensible to the frenetic life of our great cities and to the exciting new psychology of night-life; the feverish figures of the bon viveur, the cocette, the apache and the absinthe drinker?

We will also play our part in this crucial revival of aesthetic expression: we will declare war on all artists and all institutions which insist on hiding behind a façade of false modernity, while they are actually ensnared by tradition, academicism and, above all, a nauseating cerebral laziness.

We condemn as insulting to youth the acclamations of a revolting rabble for the sickening reflowering of a pathetic kind of classicism in Rome; the neurasthenic cultivation of hermaphodic archaism which they rave about in Florence; the pedestrian, half-blind handiwork of ’48 which they are buying in Milan; the work of pensioned-off government clerks which they think the world of in Turin; the hotchpotch of encrusted rubbish of a group of fossilized alchemists which they are worshipping in Venice. We are going to rise up against all superficiality and banality—all the slovenly and facile commercialism which makes the work of most of our highly respected artists throughout Italy worthy of our deepest contempt.

Away then with hired restorers of antiquated incrustations. Away with affected archaeologists with their chronic necrophilia! Down with the critics, those complacent pimps! Down with gouty academics and drunken, ignorant professors!

Ask these priests of a veritable religious cult, these guardians of old aesthetic laws, where we can go and see the works of Giovanni Segantini today. Ask them why the officials of the Commission have never heard of the existence of Gaetano Previati. Ask them where they can see Medardo Rosso’s sculpture, or who takes the slightest interest in artists who have not yet had twenty years of struggle and suffering behind them, but are still producing works destined to honor their fatherland?

These paid critics have other interests to defend. Exhibitions, competitions, superficial and never disinterested criticism, condemn Italian art to the ignominy of true prostitution.

And what about our esteemed “specialists”? Throw them all out. Finish them off! The Portraitists, the Genre Painters, the Lake Painters, the Mountain Painters. We have put up with enough from these impotent painters of country holidays.

Down with all marble-chippers who are cluttering up our squares and profaning our cemeteries! Down with the speculators and their reinforced-concrete buildings! Down with laborious decorators, phony ceramicists, sold-out poster painters and shoddy, idiodic illustrators!

These are our final conclusions:

With our enthusiastic adherence to Futurism, we will:

Destroy the cult of the past, the obsession with the ancients, pedantry and academic formalism.

Totally invalidate all kinds of imitation.

Elevate all attempts at originality, however daring, however violent.

Bear bravely and proudly the smear of “madness” with which they try to gag all innovators.

Regard art critics as useless and dangerous.

Rebel against the tyranny of words: “Harmony” and “good taste” and other loose expressions which can be used to destroy the works of Rembrandt, Goya, Rodin...

Sweep the whole field of art clean of all themes and subjects which have been used in the past.

Support and glory in our day-to-day world, a world which is going to be continually and splendidly transformed by victorious Science.

The dead shall be buried in the earth’s deepest bowels! The threshold of the future will be swept free of mummies! Make room for youth, for violence, for daring!

We Built this City on Angry, Argumentative Essays

I don't know much about architecture, nor whether or not I agree with this manifesto. But, I do enjoy angry manifestos as a form, so I'm reposting this from Bruce Sterling's blog, where he posted this in honor of the upcoming Futurist centenary.

Manifesto of Futurist Architecture

Antonio Sant’Elia (((purportedly)))

No architecture has existed since 1700. A moronic mixture of the most various stylistic elements used to mask the skeletons of modern houses is called modern architecture. The new beauty of cement and iron are profaned by the superimposition of motley decorative incrustations that cannot be justified either by constructive necessity or by our (modern) taste, and whose origins are in Egyptian, Indian or Byzantine antiquity and in that idiotic flowering of stupidity and impotence that took the name of neoclassicism.

These architectonic prostitutions are welcomed in Italy, and rapacious alien ineptitude is passed off as talented invention and as extremely up-to-date architecture. Young Italian architects (those who borrow originality from clandestine and compulsive devouring of art journals) flaunt their talents in the new quarters of our towns, where a hilarious salad of little ogival columns, seventeenth-century foliation, Gothic pointed arches, Egyptian pilasters, rococo scrolls, fifteenth-century cherubs, swollen caryatids, take the place of style in all seriousness, and presumptuously put on monumental airs. The kaleidoscopic appearance and reappearance of forms, the multiplying of machinery, the daily increasing needs imposed by the speed of communications, by the concentration of population, by hygiene, and by a hundred other phenomena of modern life, never cause these self-styled renovators of architecture a moment's perplexity or hesitation. They persevere obstinately with the rules of Vitruvius, Vignola and Sansovino plus gleanings from any published scrap of information on German architecture that happens to be at hand. Using these, they continue to stamp the image of imbecility on our cities, our cities which should be the immediate and faithful projection of ourselves.

And so this expressive and synthetic art has become in their hands a vacuous stylistic exercise, a jumble of ill-mixed formulae to disguise a run-of-the-mill traditionalist box of bricks and stone as a modern building. As if we who are accumulators and generators of movement, with all our added mechanical limbs, with all the noise and speed of our life, could live in streets built for the needs of men four, five or six centuries ago.

This is the supreme imbecility of modern architecture, perpetuated by the venal complicity of the academies, the internment camps of the intelligentsia, where the young are forced into the onanistic recopying of classical models instead of throwing their minds open in the search for new frontiers and in the solution of the new and pressing problem: the Futurist house and city. The house and the city that are ours both spiritually and materially, in which our tumult can rage without seeming a grotesque anachronism.